- Preface

- Historical/Thematic Associations

- BPH in the History of Medicine and of Mental Health Care in Ontario

- BPH as a Refelction of Ontario’s Political Culture

- Built Form/Design And Construction

- Cultural Landscapes

- Conclusion

- Endnotes

Preface

The following History was prepared for the Ontario Realty Corporation by Heritage Research Associates, Inc. in 1999. It is reproduced here in somewhat modified form. Most of these modifications concern the images, many of which did not reproduce well enough for inclusion here. In consequence, certain parts of the text have been adjusted when a mentioned image is missing or substituted in this account. For this reason, too, there are breaks in the numbering of the figures. Perhaps in the future better reproductions of the missing figures will become available and they can be restored to the text. Heritage Elizabethtown-Kitley is grateful to the Ontario Realty Corporation for permission to reproduce this report on our web site.

The report examines the heritage potential of the present Brockville Psychiatric Hospital (BPH), a provincially owned facility which has been used for the treatment of the mentally disturbed since its opening in December 1894. Located to the north of Highway 2, just east of the Oxford St. boundary between the City of Brockville and Elizabethtown-Kitley Township, it is a familiar institution in both communities. Today the eastern half of the main building complex is vacant and awaits possible redevelopment as a correctional and treatment facility or for some other as-yet unannounced use. (Phase 1 of the correctional project has been completed and is in full operation.)

The report was created with the intention of providing an overview of the property for planning and assessment purposes. It provides a basis for evaluating the site as a unit in relation to its wider community of Brockville and Elizabethtown-Kitley Township. At the same time, it establishes the parameters necessary to assessing components of the hospital as parts of an integrated entity with its own buildings and associated landscape features, an entity comparable to other institutions of a similar type in Ontario.

Physical Description

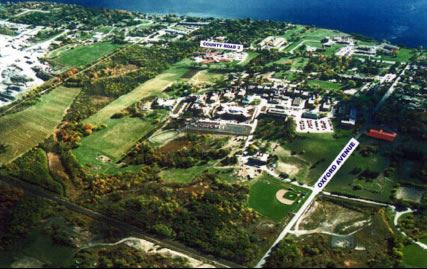

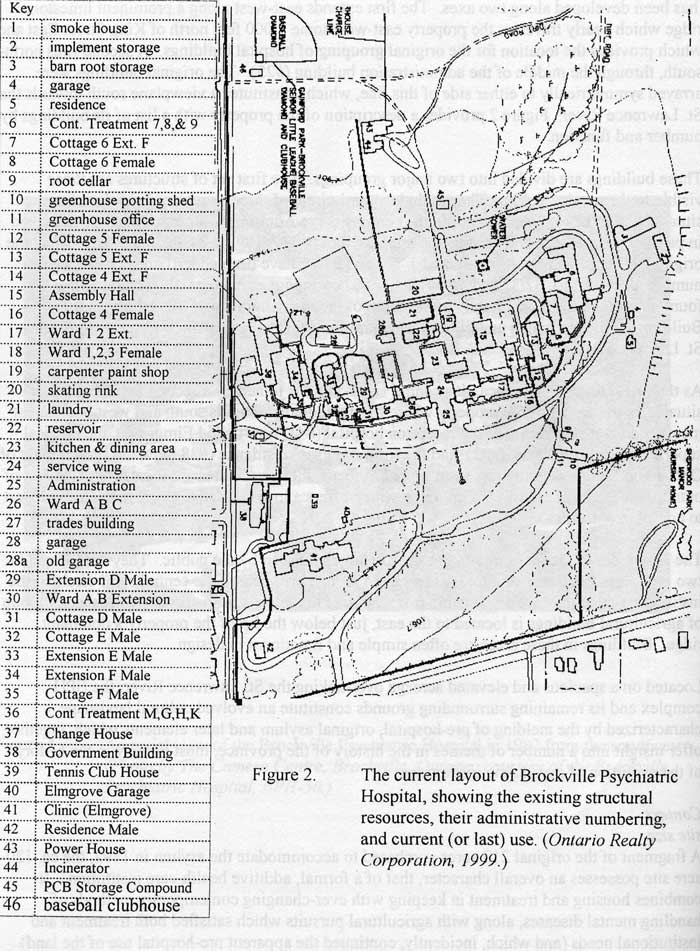

The BPH site contains 28 separate buildings (1) dispersed over a landscape of approximately 120 acres, parts of the south half of Lots 1 and 2, Concession 1, Elizabethtown-Kitley Township (2) (Figure 1). The site has been developed along two axes. The first extends east-west along a prominent limestone ridge which nearly traverses the property east-west some 1,000 feet north of King Street East and which provides the location for the original grouping of hospital buildings. A second runs north-south, through the middle of the administration building (#25). The original buildings were arrayed symmetrically to either side of this line, which constitutes a viewplane south towards the St. Lawrence River. Figure 2 provides a description of the property with a list of its buildings by number and function.

These buildings are divided into two major groupings. The first set of structures are those visible to the passing public. They include a semi-circle of three storey red brick buildings situated along the east-west ridge. In the centre sits the Administration Building (#25), flanked in parallel on both east and west by the main asylum (#s 17, 18, 23, 24, 26, and 30, to which the originally independent units numbered 14/16 and 31/29 have been added), the cottages (now numbered 8/7, 12/13. 32/33 and 35/34), and two continuous-care hospitals (#6 and 36). A fountain is set in the lawn directly to the south of the main entrance of the Administration Building, a position which underlines the central focus of the composition as it overlooks the St. Lawrence River.

As the institution’s public face, this central semi-circle is joined by a second set of buildings situated in the corner of the property where formal fencing along its south and west boundaries meets. This set is made up of the reception hospital (#41, now called Elmgrove), the medical superintendent’s residence (#42), and the former nurses’ residence (#38, now the Government of Ontario building). Slightly less institutional in focus, these structures are located in the midst of outdoor recreational facilities, a grouping which offers a low-key activity link in the area closest to community traffic.

The remainder of the buildings on the site are largely unseen by the public. They are located in two groupings. Service structures are situated to the north behind the central semi-circle of the institution where they are only visible from the road to the west of the property. A second group of agricultural buildings is located to the east, just below the lip of the property’s dominant ridge. Buildings in these areas are often simple and functional in design.

Located on a spacious and elevated acreage overlooking the St. Lawrence River, the BPH complex and its remaining surrounding grounds constitute an evolved cultural landscape characterized by the melding of pre-hospital, original asylum and later elements which, together, offer insight into a number of themes in the history of the province, most notably in the history of the evolution of psychiatric institutions.

Site Size

A fragment of the original 219 acres purchased to accommodate the asylum in 1892, the ca. 120-acre site possesses an overall character, that of a formal, additive health-care institution. It combines housing and treatment in keeping with ever-changing contemporary methods of handling mental diseases, along with agricultural pursuits which satisfied both treatment and institutional needs (and which, incidentally, continued the apparent pre-hospital use of the land). The setting is a combination of wooded parkland for the “public face” and farmland, bush and scrub elsewhere.

Portions of the original property are no longer administered by the hospital. These include the 20 acre waterfront area between King Street East and the St. Lawrence River, transferred to the city in the 1960s and 1970s; a lot in the southeast corner of the property, north of King Street East, which became the site of a long-term care residence (Sherwood Park Manor); and a 60 acre section of farmland, located north of the railway.

Grounds

There are strong reasons to believe that the asylum was located near Brockville for political reasons (3). Nevertheless, the nature of the landscape is often as important as the built heritage on a property of this size. This is especially true at asylums of the late-19th and early-20th centuries, where tranquil surroundings, land- and water-based recreations, gardening and agricultural activities played both therapeutic and institutional roles. Like many other such institutions, BPH was located in an obviously rural setting immediately adjacent to an urban centre. Its land gently rose from the river to the crest of the ridge on which the original administration, main and cottage buildings were placed, and then fell away to the north and east. The character of the land was judged exceptionally appropriate for such a facility, especially the presence of water that could be viewed from a height. Ontario asylums at Kingston, Penetanguishene, Whitby and Mimico were directly on the water, while other institutions at London, Hamilton, Cobourg and Whitby all had sites within several miles of the water.

In the type of “moral treatment” practiced in provincial asylums at the end of the 19th century, vistas of water and of rural landscapes were thought to possess a calming effect on the overactive and over-stressed minds of the mentally disturbed. At Brockville, noted the Chief Architect, Kivas Tully, “the view from the site in all directions is very extensive and very … attractive, and especially so to both eastward and westward, whence in both directions can be seen splendid and magnificent stretches of the River St. Lawrence.”(4) Following the tenets of moral therapy, patient activities such as sailing, walking, gardening and playing low-key sports, such as tennis and lawn-bowling, all played an important role in the cure of the disturbed. (5) Gently curving paths and roadways, extensive beds of flowers, fountains and other water features, garden buildings such as gazebos, and plantings of hedges, bushes and groves of trees were all important elements in the workings of an asylum, for they offered both an opportunity for treatment and an attractive setting for patient activities. The skeleton of this landscape survives, as do many of its individual elements, including the network of path- and roadways, the cast-iron fountain, the boundary wall, and many of its plantings.

Placement

As noted previously, the site has been developed along two axes. The first, which extends east-west along a prominent limestone ridge which nearly traverses the property east-west some 1,000 feet north of King Street East, offers a site for the original grouping of hospital buildings. From the second, which runs north-south, through the middle of the administration building (#25), the original buildings were arrayed symmetrically to either side of this line. The site’s dominant landscape component is that east-west stone ridge which rises some 154 feet above the river level. These two axes have imposed a cross-like orientation on the site that both inspired its original conception and anchored its long-term development. No other Ontario asylum possesses the advantage of having such clear and dominant axes – north-south to the river, and east-west along the ridge – as the Brockville institution does. Other institutions are oriented towards the roadway on which they are placed, or (when they exist) towards water courses, or are confused in their orientation, some buildings facing the road and some the water. (The institution at Hamilton is distinctive as well in its placement of the edge of the escarpment; its confusion is between the street front and distant views of the lake from the heights of the escarpment.)

At Brockville, the ridge, terraced and formalized, provides the location for BPH’s most impressive structural component, the hilltop range of original hospital structures, consisting of the administration, main and six cottage buildings, arrayed in a gently curving crescent on the crest of a ridge. This impressive grouping was erected in 1892-94 and has been expanded considerably since, notably during the 1950s, when floor space increased by nearly 50 per cent. The gently sloping land south of the ridge has evolved from an uneven sector of wild land into a parkland sector of mixed trees, lawns and plantings of a type often found on estates at the turn of the 20th century. Here a secondary grouping of structures were placed, including the medical superintendent’s residence (#42, built in 1896), the reception hospital (#41, now the Elmgrove Clinic, 1913-15), and the nurses’ residence (#38, 1931-32).

Perspective

This impressive site has always been viewed by the public from the old Prescott Highway (King Street East), which runs along the southern edge of the site, about 1000 feet south of the ridge. Today, maturing trees obscure the original vista of the main grouping of buildings occupying the impressive terrace atop the transverse ridge. At the same time, this natural condition gives the institution greater privacy.

Continuity

The institution’s function as an asylum (or place of refuge), the size of the site, and the facility’s placement outside what were then the boundaries of the city of Brockville – all these factors have combined to make BPH into a community, or island, set apart from the greater community of the City of Brockville and of Elizabethtown-Kitley Township where it is officially located.(6) The BPH has possessed an important influence on the surrounding community, rather than the more traditional heritage relationship, of the neighbourhood having a definable impact on the property under study (see “History” below). Local architectural historian Doug Grant has pointed out the similarity between the main building at BPH and at least one Brockville building, Publow Terrace (7) (Figure 3 [missing]). Since this row house was constructed after the BPH structure was completed in 1892-94, the hospital seems to have provided inspiration for its design

HISTORICAL/THEMATIC ASSOCIATIONS

The following historical themes, both local and provincial, appear to be reflected in the establishment and development of the Brockville Psychiatric Hospital.

Local Development

Though its function and design set this hospital apart from both the Brockville and Elizabethtown-Kitley Township communities, BPH has always been considered to be a local asset. From the beginning, reasons for this were both economic and psychological. Economically, the institution promised money in construction, employment and supplies. Emotionally, it was a source of local pride.

Economic Role

Brockville newspapers recognized that it would be impossible for regional builders to garner many of the contracts for so large a project – indeed, the main construction contract was awarded to the low bidder, Garson, Purser & Co. of St. Catharines at a bid of $241,438 exclusive of heating, water, sewage and outbuildings.(8) But local suppliers figured prominently in the awarding of subcontracts, and workmen from Brockville and area received considerable work from this construction project.9) This fulfilled the promise made by the Brockville Recorder that “the building of this institution will cause a considerable expenditure in our midst ….”(10) This input to the local economy continued in later construction, where Brockville area builders actually obtained the contracts for buildings such as the medical superintendent’s residence (#42, 1896) and the assembly hall (#15, 1910-12).

Employment was another important element in the relationship. While the senior staff almost invariably were promoted to posts in Brockville from other institutions, attendants and other employees were often appointed from among the local population. A total of 41 staff were selected during the first year of operation and, while places of residence were not provable in all cases, at least a majority of these individuals came from the immediate area. Historically, the institution was especially notable in the local context as a prominent employer of women, who normally found it difficult to find appropriate paid work outside the home. The asylum hired female attendants, laundresses, secretaries and switchboard operators, largely from the local population. The School of Nursing, established in 1903 and limited to female applicants until 1957, offered further opportunities for the training and employment of women. This emphasis on BPH as a source of jobs grew dramatically as the institution shifted from being a refuge to being a centre of psychiatric medicine. By 1972, the hospital had grown to be one of the region’s largest employers, with a staff of 840.

Supplies were a third area of interaction. Though asylums were designed to be communities unto themselves, the institution depended upon Brockville and area for items that it could not provide internally. When the hospital’s founding was announced in 1892, the Brockville Recorder, the local mouthpiece for the ruling provincial Liberal party, promised that “the annual expenditure in the way of local supplies and wages [after the asylum opened] would reach a large sum.(13) The expenditures were immediate: the institution hooked up to the municipal water, gas and, later, electricity and sewer connections and tendered locally for a wide range of items such as coal, wood, cloth, linens and other goods from Brockville and area suppliers. The economic relationship was a two-way street: the asylum also produced surpluses which were offered in the local marketplace. In only its second year of operation, for example, the farm produced nearly four tons of pork, of which little more than half a ton was required for institutional purposes. The gardens also produced tomatoes, carrots and other vegetables in quantities far beyond the hospital’s needs.

Like other institutions of its type, BPH has undergone considerable structural change during its history. Shifts in the philosophy of the treatment of the mentally ill help to explain some of these modifications, but politics and the economy often justify the timing of specific changes, for asylums were (and are) products of the political system. The establishment of the hospital at Brockville (rather than elsewhere in eastern Ontario) was, almost certainly, primarily a political decision, and most hiring and contracts there had political, as well as institutional, implications.

Community Pride

Finally, the construction of the asylum at Brockville was a source of enormous civic pride, and BPH remains an important regional institution in the eyes of local leaders. Historically, the choice of this area as the site for a major governmental institution – rather than its eastern Ontario rival, Ottawa – confirmed the city’s status as a regional centre of importance and reminded local residents of its advantages as a transportation hub with excellent connections by rail and water to Toronto and Montreal. Brockville was the capital of a region substantially more populous than Ottawa and was a major focus of manufacturing and commercial activity. Some considered it the richest urban centre in Canada.(15) Strategically positioned along the river, main highway and rail line, the asylum would be “one of the most prominent features that will be noticed by the traveller up or down the St. Lawrence ….”(16) The asylum was the only Brockville institution to merit a two-page treatment in the 1895 promotional publication, Brockville Illustrated.

BPH has a lively sense of its own heritage. It has a museum room, in which are displayed original architectural plans, photographs of people and hospital buildings from various periods, and artifacts ranging from official records to medical instruments to decorative elements from demolished structures. In preparation for its centenary in 1994, the psychiatrist-in-chief, Dr. R. Draper, carried out research into the institution’s past and prepared two academic papers on important aspects of its formative years: the place of BPH in the development of Ontario’s asylums, and the characteristics of a sample of early patients.(18) For the centenary itself, senior management authorized expenditures in support of researching the history of the institution and its place in the development of mental health care in Ontario. One result of this initiative was the production of a series of attractive and informative historical panels which currently line the entry corridor of the administration building and introduce both visitors and staff to the rich heritage of this institution. Another has been creation of a collected Book of Memories.

BPH in the History of Medicine and of Mental Health Care in Ontario

BPH stands as an example of the prevailing late 19th-century approach to the care of the mentally ill in Ontario. It was designed according to the standards of “moral” therapy, an approach to patient care popular during the second half of the 19th century, but soon to be superseded by more interventionist treatments.

Moral Therapy

Briefly, “moral” therapy involved treating the mentally ill with humanity and compassion in a home-like setting, in contrast to earlier, “heroic” approaches to the handling of the mentally ill. “Heroic” treatment was based on the notion that the patient’s disturbed mental state could most effectively be rebalanced by physically shocking the individual back to normal. These “shocks” to the system included burning (blistering), bleeding, whipping and quick immersions in cold baths. The use of force and physical restraint were integral parts of “heroic” treatment, and buildings erected to accommodate its techniques most closely resembled prisons in their architectural character.

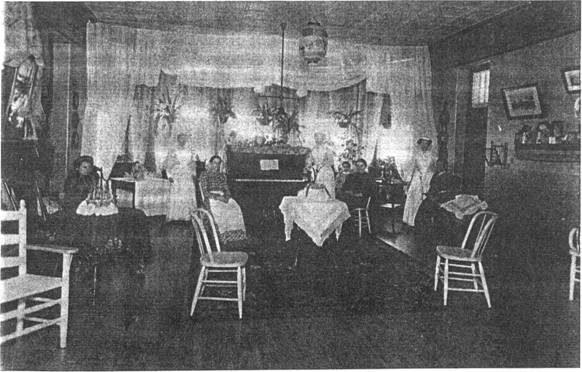

The rise of “moral” treatment is broadly connected with the influence of the American alienist, Dr. Thomas Story Kirkbride, who developed an overpowering influence in North America in the handling of the insane and, especially, the type of hospital design required to fulfill then-current mental health-care objectives. “Moral” therapy, on the other hand, believed that diseased minds could be returned to normalcy by care of the body coupled with the absence of stress and the imposition of a regular routine. “Moral” treatment saw the role of the institution as returning the patient to a state of normalcy (or morals) by providing a stable environment, heavily rule-bound, in which the individual made very few, if any decisions.(20) Set times for eating, sleeping, work and recreation, a regular routine of activities, and an absence of decision-making regarding the myriad of normal daily details, from dress to meal choices to bedtimes, would reduce the strain on the disturbed patient. Daily routines focussed on low-stress pursuits, always well supervised, such as gardening and other forms of horticulture; indoor activities such as sitting, simple games such as cards and checkers and, for women, sewing; and outdoor recreations thought to be relaxing, such as walking, boating, lawn bowling and tennis. These outdoor activities placed the patient closely in touch with nature, which was itself thought to be a great healer of diseased minds.

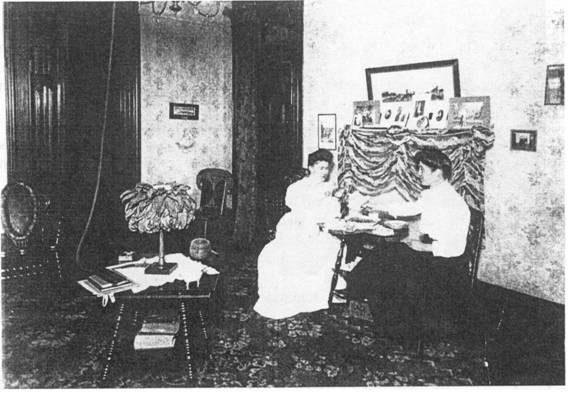

BPH is a late example of an institution designed according to the principles of “moral” treatment. It was a “mixed” asylum, placing those in need of acute care in the main building and relegating long-term, chronic-care patients to the six cottages, the three to the west allocated to men and those on the east to women. Wherever they were placed, patients originally lived quite comfortably. As Doctor R. J. Draper noted in 1992, early photographs of the interior of Brockville bear eloquent testimony to the influence of “moral” therapy. Heavy drapes, lace, potted plants, pianos, [and] comfortable furniture create an image more akin to a Victorian sitting room than a hospital ward. The day was spent at work whilst the evenings were given over to concerts, music, [and] dances. The preservation of patients’ dignity was paramount. There was very little restraint …. It should be noted too that the first patients all had individual rooms.

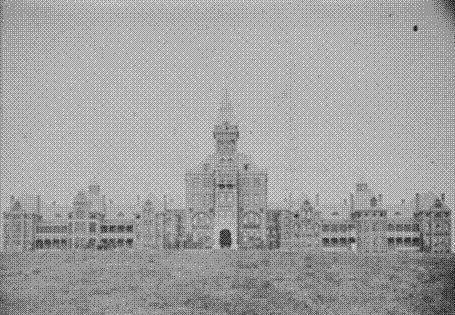

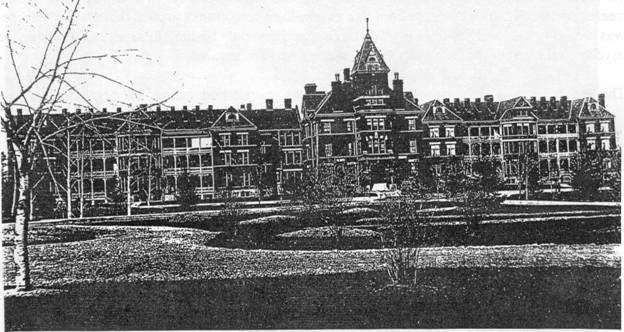

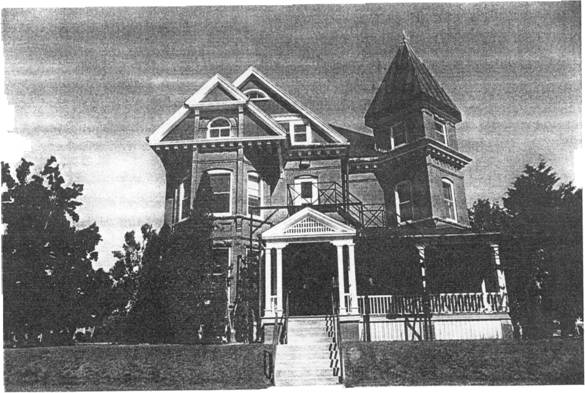

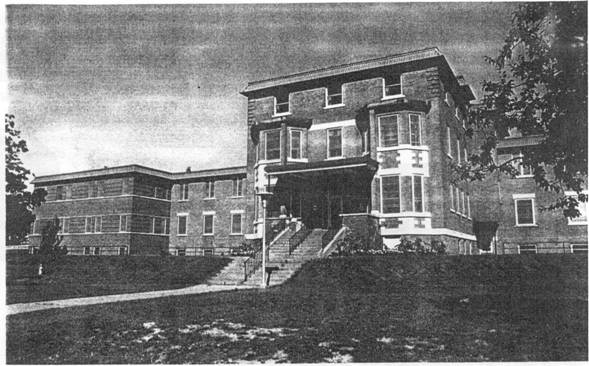

The external character of this early institution is illustrated in Figure 4 and Figure 5, while the original internal appearance of the administration, main and cottage buildings is shown in Figures 6, 7 and 8.

As a result of massive structural changes undertaken in the 1950s, it is now nearly impossible to see the design requirements of “moral” therapy in the present buildings at BPH. There are several earlier institutions, notably the current Kingston Psychiatric Hospital, whose first building was begun in 1859,(23) which appear to illustrate the architectural standards of “moral” therapy more clearly. Indeed, in his recent study of asylum design across Canada, the architectural historian James De Jonge concluded that “the former Rockwood Asylum in Kingston, Ontario … is the only other purpose-built institution from the pre-Confederation period to retain most of its original design qualities.(24) The demolition of the primary subject of his report, the former Provincial Lunatic Asylum in Saint John, New Brunswick (founded 1835, opened 1848) makes the Kingston complex unique, and of considerable significance in the national context.

Later Stages of Psychiatric Medicine

“The broad spacious corridors and rooms designed to allow the free entry of air and light are no longer found in the cramped cost-saving buildings of today,” moaned Dr. Draper in 1992.(25) Growing numbers of patients and, more importantly, dramatic shifts in the practice of mental health dictated those changes, which can be briefly summarized. At the turn of the 20th century, the rise of Freudian psychology and the experiences of the First World War challenged the bases of “moral” treatment, which argued that insanity was organic and could be cured primarily by treating the body with kindness. Freudian psychology, in contrast, argued that mental disease was rooted in the experience of psychic trauma and that only by lengthy analysis of one’s inner psyche could the roots of a person’s mental problems be revealed.

The horrific wartime experiences of Canadian soldiers also undermined the organic basis for mental illness. While some doctors argued that the symptoms of mental distress, or shell shock, were generated by the impact of exploding shells, which caused physical changes in the body which, in turn, led to mental problems, research – which uncovered many cases of shell shock(26) among those who had never undergone fighting at the front – suggested mental, and not physical, roots for the symptoms of shell shock. The growing acceptance of the theoretical underpinnings of Freudian psychology led asylum doctors to study their patients and explore their mental natures through the media of tests, interviews and observations. In the 1940s and 1950s, the growing evidence of medical testing and experimentation led doctors, once again, to see a possible physical root to mental illness. While Freudian analysis continued to be popular among private psychiatrists, those working in the public health care field focused on a succession of treatments – electro-shock, frontal lobotomies and, increasingly, mood-altering drugs – which attempted to deal with mental problems as the external expression of an internal, and largely physical, imbalance or distress. Treating the external symptoms of distress -unacceptable behaviour – became the professional focus of the institution.(27) Today, these thrusts have been transformed into an emphasis on de-institutionalization, community-based mental health programs, and drug therapy.

BPH as a Refelction of Ontario’s Political Culture

sponsiblity for Care of the Mentally Ill

BPH is one of several examples which, individually and collectively, help to illustrate the position taken in Ontario on issues relating to state intervention in personal matters. The British North America Act (1867) gave the provinces the power to legislate in the “establishment, maintenance, and management of Hospitals, Asylums, Charities, and Eleemosynary in and for the Province, other than Marine Hospitals.”(29) But the political culture of each province determined how this power would be exercised.

From the first efforts to provide for the needs of what were then called “the insane” in 1830, Ontario has broadly accepted the principle that the care of the mentally troubled was a provincial, rather than a private or local, responsibility.(30) This commitment to provincial support for the care of the mentally troubled (variously defined) rested on the notion that mental illness was not a personal or local problem, but an affliction for which the whole society bore some responsibility. This acceptance stands in contrast to the province’s traditional position on the care of the sick, which generally placed that responsibility at the local level, though sometimes with provincial financial support. Toronto’s acceptance of primary responsibility for the care of the mentally troubled had important structural implications: it led to the establishment of a series of institutions financed largely by general taxation and placed under provincial management.

Provincial Institutions

The first of these asylums was located at Toronto (1839; a purpose-built asylum dates to 1850), followed by institutions at Kingston (for the criminally insane, 1856; purchased from the federal government, 1877), Fort Malden (1859), Orillia (for the feeble minded, especially juvenile cases; originally opened in 1859, reopened in 1876), London (1870), Hamilton (originally for alcoholics, 1876), Mimico (1890), and Brockville (1894). Before the Second World War, the system was expanded by the opening of asylums–which, after 1914, were termed Ontario hospitals–at Cobourg (for females, 1902), Penetanguishene (1904), Woodstock (for epileptics, 1906), and Whitby (1919).

BPH is a physically imposing example of Ontario’s decision to support a system of institutions for the care of those defined as “mentally defective” – whether through accident, disease, heredity or alcoholic abuse. In a province traditionally characterized as small-c “conservative” in its political culture, this acceptance of responsibility for personal affliction stands in contrast to a general reluctance to intrude governmentally in cases of individual need.

The BPH as an institution speaks directly to this theme: it is visually a piece of official architecture, designed by the office of the Chief Architect of the Department of Public Works. Its design is characteristic of provincial work in the field of asylum architecture. In its external appearance, placement and construction, the original structures (and their successors) were uninfluenced, to all appearances, by local design and building traditions. Instead, they embody provincial standards which, in turn, were derived from sources external to Ontario. A community unto itself, BPH consistently utilized architectural modes which were not commonly found in and around Brockville. The institution was, instead, an expression of provincial aspirations and prevailing medical theories worked out in a specific locale.

Built Form/Design And Construction

Introduction & Site Definition

Though there were often variations in form and layout, Ontario asylums until the Second World War tended to include a fairly uniform range of structures with a consistent hierarchy of site importance. Components of primary functional importance were usually prominently sited in structures of advanced architectural quality. At asylums, these consisted of two elements: institutional administration (which initially did not require large spaces), and the quarters devoted to patient treatment and housing (which did). At the second level in siting and architectural quality stood staff residences, clinics and other elements of patient support. Structures which were used in the institution’s farm operations usually were centered in a single compound and possessed a measure of architectural elaboration, while recreational facilities normally occupied spaces adjacent to patient living quarters and tended towards the functional in design and appearance. Finally, institutional support services – garages, workshops, and other services – usually occupied the least prominent positions on the site and their exteriors and interiors were architecturally the least prepossessing. This is the pattern of built resources at Brockville.Here, the clarity in the organization of the site and the quality of the original design were enhanced by the character of the site, which featured a high east-west ridge. As elaborated by later landscape changes, this provided the location for the most important structures which, in turn, hid the service structures to the north.

Unlike other institutions, whose original clarity of overall plan was gradually eroded by later additions, this organizational pattern has been reinforced in the progressive expansion of BPH. Institutional expansion is found at almost all of Ontario’s mental health centres. As medical and management ideas evolved, institutions were required to change bringing additions to and renovation of existing places, construction of new medical and service facilities, and demolition of outmoded structures. At Brockville, these changes took place within the functional form of the existing institution. Such is not the case elsewhere. In other provincial institutions, they occurred in a haphazard fashion causing a lack of functional focus and order in the postwar period.(32) Brockville seems to be an exception to this pattern.

With this hierarchy and its high degree of integrity in mind, the following discussion will examine the design and construction qualities of buildings on this site according to the functional breakdown described above: administration and patient treatment/residential, institutional support, farm operations, patient recreation, and institutional support.

Administrative and Patient Treatment/Residential Facilities

Original Facilities

The original administrative/treatment/residential complex was designed as a single grouping of structures and embodied the architectural characteristics of a modified cottage hospital of the late 19th century (Figures 4 and 5). For the layout and design of the administration and main buildings, the Chief Architect reportedly utilized the plans and elevations of an existing operation, the Connecticut Hospital for the Insane at Middletown Connecticut, which had been erected in 1880-81.(33) This American structure also inspired the design of the Orchard Building at Hamilton

After the Second World War, the increasing emphasis on medical, rather than mental, causes for psychiatric illnesses led provincial officials to transform the Ontario Hospital at Brockville in stages from the refuge it started out to be into the hospital it was to become. In structural terms, the most significant aspect of this transformation took place during the period between 1949 and 1957, when the government funded a vast expansion, renovation and fireproofing program that left hardly any of the original building fabric unchanged. The buildings we see now reflect the shifts in the treatment philosophies which have emerged during the past century.

Both the Brockville and Hamilton examples consist of a central administration building measuring 60 feet square, two storeys plus attic in height and dominated visually by a prominent seven-storey tower and a fronting porte-cochere. Placed some 50 feet behind the rear of the administration building, and linked to it by a one-storey passageway, was the “main building,” a two-storey treatment facility for acute-care patients, 400 feet long and 50 feet deep (now #s 18, 23, 24 and 26). The rear elevation was marked by projecting wings, 72 feet wide, for dormitories and dining halls. Behind the centre pavilion sat a deep service wing, 200 feet long and 40 feet wide (now replaced by #23).

Chronic-care patients – those requiring long-term accommodations and constant supervision but minimal treatment – were placed in cottages arrayed, three to the east for women and three to the west for men, on either side of and in a progressively more recessed arrangement slightly behind, the main building. These are now numbered 8, 12, and 14 on the east side and 31, 32 and 35 on the west. Fronted by wooden verandahs which contributed to their domestic appearance, the two-storey brick cottages were identical in plan and elevation, measuring 80 feet across by 40 feet deep with projecting dining room wings behind of 42 feet by 28 feet.

As built, the core buildings at BPH possessed a reasonably uniform appearance based on the consistency in architectural design and decorative approach, in the harmonious scale of the individual buildings, and in the predominant material used, a warm red brick. Part of the “public face” of the institution, these structures were designed in one time period by a single office – the architectural staff of Ontario’s Public Works department under Chief Architect Kivas Tully – as a unified composition or assembly of architecture. The use of the ridge traversing the property as the site for the “public face” of BPH distinguishes this institution in comparison with other Ontario hospitals. Because the main components of these original buildings survive (albeit, in a much modified form), and because additions were generally compatible in style, scale and materials, this range likely possesses more design aesthetic cohesion than other groupings of extant asylum buildings.

In describing these buildings, the Chief Architect ascribed no definite architectural style to them, for the very good reason that they belonged to no single design approach. They possess the eclectic mixture of forms and details and the rhythm of receding and projecting elements characteristic of the Queen Anne Revival, but it is not a pure example of this design approach.(35) In keeping with the approach of Queen Anne design, these units possess the irregular roof and wall pattern, in the form of towers, gables, chimneys, projecting and receding pavilions and varied shapes in openings. Surface richness was achieved by the use of a variety of materials, including stone, terra cotta and stained glass. But the building lacks the characteristic asymmetry associated with the Queen Anne and, perhaps because it was official architecture, instead utilizes the regularity and balance of forms drawn from classical principles of architecture. (The use of classical principles in the placement of elements is clearer now that the original verandahs have been removed from the fronts of the main and cottage buildings.) Different materials were simply used as decorative accents and not, as the advocates of the Queen Anne Revival considered essential, as components in the building’s overall design. The result is a group of original buildings coherent in their conceptualization and consistent in their scale, method of decoration and materials.

1950’s Change

The appearance of the main buildings of BPH remained relatively consistent during the first half of the 20th century. In the 1950s, however, major changes were made to the external appearance of all components in this grouping, and two identical modern new components of institutional design have been added, the male (west) and female (east) continuous treatment facilities (respectively, #s 36 and 6, both built in 1957-59). The tower of the administration building (#25) was taken down to the roof in 1938, the porte-cochere was removed and replaced by an unsympathetic aluminum version in the 1970s, and the building was extended where the link had previously been to integrate this structure with the main building behind it.

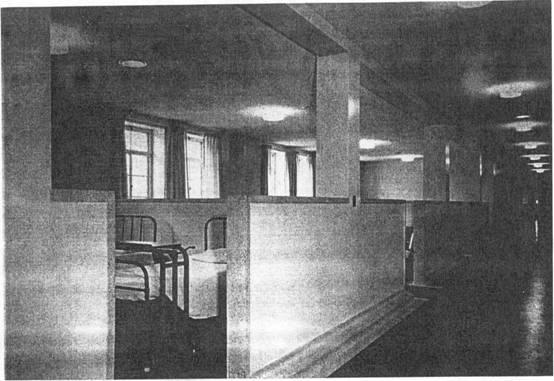

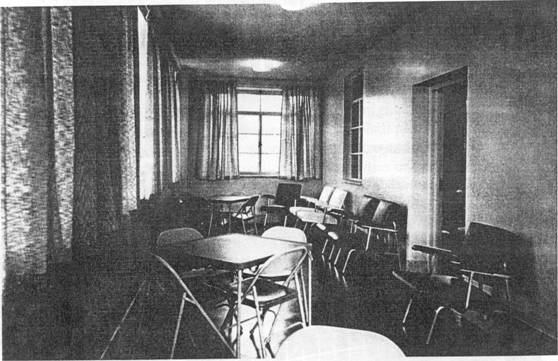

The main building (#s 18, 23, 24 and 26) has been more radically altered. It was linked to the first cottages to either side by concrete and steel verandahs in 1908-10; during the 1950s, these links were taken down and patient wings inserted in their place (#s 17 and 30). A third storey was added to the main building, also in the 1950s, and the character of the fronts modified by the removal of the verandahs. The interior was removed and the original arrangement of single rooms, dormitories and service areas was replaced by a centre-hall plan, ward-style hospital constructed in modern materials, such as steel, concrete, terrazzo and tile. The original character of an asylum, with its attempts to replicate the amenities of middle-class life within an institutional setting, was replaced by the modern appearance of a ward-styled hospital. Compare Figures 6, 7, and 8, which show the original living spaces characteristic of the asylum, with Figures 10 and 11, which show the 1950s approach to the treatment of spaces. The service wing behind was replaced by a much larger kitchen, cafeteria and laundry pavilion (#23), also in the 1950s.

The cottages have perhaps undergone the greatest changes to their appearance. During the 1950s each cottage was altered externally by the removal of their original verandahs, the modernization of windows and the construction of new entrances, whose glass-block and patterned brick forms of decoration speak directly to their period of construction, the 1950s. The floor space of the cottages was roughly doubled by the construction of long wings to the rear, and the fronting cottages were gutted and reconstructed as ward-styled hospitals using steel and concrete. The original construction technologies have been superseded by modern ones. Comparing Figures 14 and 15 illustrates clearly the nature of the changes made.

Admittedly, this reconstruction program possessed some sensitivities to original fabric. These additions carry on some of the design motifs of the original buildings, especially in their use of a cherry-red brick which is consistent with initial work. Some original design elements, such as the terra cotta inserts, have been retained and the footprint of the original buildings largely survives. But the character and clarity of the original design has been lost and it is difficult to “read” these structures as originating in the 1890s.

Institutional Support

Three key buildings supporting the original institution were erected on the property between the main complex and public roadways at both Highway 2 (King Street East) and Oxford Street. They were the medical superintendent’s residence (#42, built in 1896), the reception hospital (#41, now the Elmgrove Clinic, 1913-15), and the nurses’ residence (#38, 1931-32). Lightly shielded by fences and trees, these structures served as a transition between the community and the institution, although all were located on the periphery of the institution itself so as not to obscure views from Highway 2 of the main complex on the crest of the hill. They served respectively as a house for the institution’s chief administrator, an evaluation centre for new patients and a medical clinic/operating room, and a school of nursing to train female staff (men were not admitted until 1957) for advanced psychiatric patient care roles within the institution.

With its irregular outlines, broad verandahs and profusion of decoration, the medical superintendent’s residence (#42, Figure 17) adapted the Queen Anne Revival design approach of the original main buildings, interpreted on a domestic scale but without the classical elements. The design is straightforward and competent, but its walls are smooth surfaces of brick and lack the complexity of surface treatments characteristic of the best of Queen Anne Revival design. Its interior, on the other hand, remains quite elegant, with broad marble fireplaces and elegant wood- and plaster-work.

Though both are fine pieces of Edwardian Classical design, the reception hospital (#41, Figures 18, 19) and the nurses’ residence (#38) vary somewhat in form, probably because of their differences in period – pre-First World War and the beginning of the Great Depression, respectively. Except for an untraditional profusion of windows enclosing the verandahs – a design choice necessitated by the building’s function – the reception hospital is similar in scale and decoration to many homes of the well-to-do built during this time period. The nurses’ residence is somewhat more severe in its handling of decorative forms – a reflection, perhaps, of its late date of design.

In spite of changes in function, two of these buildings – the former medical superintendent’s residence (#42) and the nurses’ residence – retain many of their original design qualities. Their building footprint, their exterior appearance, their interior plan, their exterior decorative treatment and many interior finishes – have largely been retained.

The reception hospital is barely recognizable as a pre-First World War structure because so many of its original features were removed in major renovations and extensions completed in 1958-59.(36) The result is a structure which, in its appearance, scale, materials and method of construction, speaks to the 1950s, rather than to its original date of construction.

The Farm Compound

For both operational and therapeutic reasons, farming was an intrinsic part of Ontario’s asylums (except at Toronto) during the 19th and early 20th centuries. At Brockville, the head farmer was one of the first institutional officers hired, and the initial buildings within the agricultural compound were among the pioneer structures to be planned and completed.(37) Between 1910 and 1967 this compound also served as the central on-site facility for two remote farms – one adjacent to the existing property but north of the railway line and a second, “the Stagg Farm,” north of Highway 401. Once intrinsic parts of the BPH operation, these two properties have since been sold. In spite of these losses, it is still possible to see remnants of agricultural fields to the north and east of the hospital site.

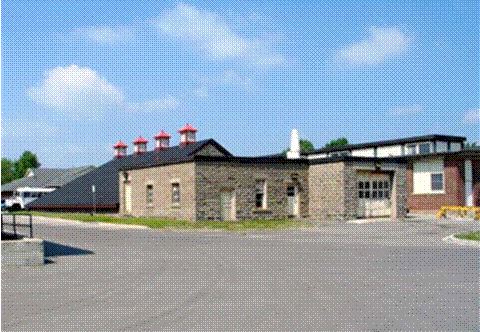

The agricultural compound originally consisted of four structures: the bank barn (#3, Figure 21), the slaughter house (#1/2), the piggery (demolished) and the head farmer’s house (#5). Once completed, they were judged to be “of handsome design, and well adapted to the purposes for which they are intended.”(38) Eventually, the agricultural compound expanded to include a greenhouse, potting shed and office (#9/10/11, 1917), a garage (#4), and a series of frame sheds. With the exception of the piggery and the sheds, all of these units survive.

This is an impressive grouping of buildings in its design, treatment of materials, and appearance. Located immediately east of the last women’s cottage and almost hidden from view under a high bluff,(39) the original farm buildings replicate the arrangement of a typical Ontario farmyard, with the house placed well before a farmyard enclosed by the barn and slaughterhouse. The fronting element, the head farmer’s (sometimes referred to as the gardener’s) house (Figure 22), was originally a well-designed version of the province’s most common 19th-century house type, the Ontario cottage.(40) This formula, popular from the 1820s until after 1900, consists of a modestly scaled 1 1/2 storey side gable residence with a balanced facade, a gable or (more rarely) a dormer over the door, and a sprinkling of (usually Gothic Revival) decoration. The drawing for the front elevation of this building is very similar to those published for “a cheap country dwelling house” in the 1865 edition of the journal, The Canada Farmer.

Constructed of cut stone with concrete floors at the impressive cost of $24,000, the barn and slaughterhouse are much larger and more sophisticated than one would expect on the average farm of the 1890s. The two-storey bank barn (to which a five-sided root house was added in 1898) measures 159 feet long by 40 feet wide, while the slaughterhouse is a one- to two-storey structure, 90 feet by 30 feet.(42) In keeping with the design of most farm buildings, these two structures include few explicit stylistic references, though the bank barn’s classically balanced facade is carefully composed. Both depend on their considerable scale and their high standards of craftsmanship, especially in the execution of the stonework, for their architectural effect.

With the exception of the 1898 roothouse addition and the enlarging of the main door on the bank barn at an unknown date, departmental and institutional records suggest that relatively few structural modifications were made to either building. Now used for machine storage and maintenance, they continue to function much as they did in the early days of the asylum. The greenhouse, potting shed and office (#9/10/11, 1917) are simple structures, unpretentious and functional in design. They appear to retain a high degree of integrity.

Recreational Facilities

A key component in “moral” therapy was the use of relaxing and enjoyable games and activities as diversions from the stresses of everyday life. “It is a fact universally recognized that curable cases are largely influenced by such matters as amusement, recreation and occupation,” noted the medical superintendent in 1906.(43) From this perspective, the notion of an asylum was not limited by the bounds of structures: the entire property became an agency for therapeutic treatment. Early records document recreational activities such as strolling the grounds, reading, card playing, and games (dominos, draughts, cribbage, checkers, and chess were all popular).(44) Outdoor pleasures usually involved an interaction with that great healer, Nature. But, to be truly effective, Nature required human intervention; it needed to be structured, tamed and ordered, just as life within the asylum was.

A key agent in the transformation of the appearance of the asylum property was Dr. J. B. Murphy, the institution’s first superintendent, who held office from late in 1894 until his death in January of 1904. For the almost five years before his appointment to Brockville, Murphy has served as the founding administrator at the cottage hospital for the chronically insane at Mimico. There, he had already implemented the essential components of “moral therapy,” and his work at Brockville elaborated on his close understanding of the physical requirements of this treatment approach. “His practical adaptability to work in connection with the establishment of the new hospital, as evidenced [at Mimico],” Henry Hurd has noted, “caused him to be made superintendent at Brockville, and the improvements made in his regime [at Brockville] are a lasting tribute to his memory.

With the institution’s original buildings already designed and virtually complete when he was appointed its head, Murphy focused his efforts on the selection of staff, the administrative organization of the asylum and, particularly, on the arrangement of its landscape, largely in the area between the ridge and King Street East. In the first years of operations, Murphy’s annual reports pointed to the establishment of a system of roads and pathways, the clearing of boulders and underbrush, the levelling of rough ground, the seeding of lawns, and the establishment of beds and other plantings. The “public” boundaries along King Street East and Oxford Street were defined by formal stone walls and gates, while other property lines were fixed by fences. These landscaping efforts, completed almost entirely by the patients working under the institution’s chief gardener, yielded notable and welcome improvements in the appearance of the grounds. But, more importantly, they achieved therapeutical goals, for “employment judiciously apportioned is also a powerful aid towards recovery”.

After Murphy’s death, his work on the development of the landscape was taken up and completed by his successor, Dr. Thomas J. Moher, who superintended the terracing in front of the main buildings (“in accordance with the plans of Mr. Houston, landscape gardener”(47)), further grading and seeding of the parkland further south, and the construction of new path- and road-ways. By 1910, the work begun under Murphy was judged by Moher to be complete.

Even though medical staff agreed that “we recognize the utility of a limited amount of labour and employment as a curative agent in the treatment of [the] insane,” staff argued that “diversion for the mind while the body rests is quite as essential.”(49) In planning the landscape, provision was made for the installation of flower and vegetable gardens, orchards, walkways, sitting areas, tennis courts, bowling greens, and a playing field. All of these were designed to offer pleasurable outdoor activities for able-bodied patients. Indoor recreation also played an important role in the therapeutic program. In the main, these required little new construction, though some amusements required new facilities; the construction of a skating rink (#20, 1904) and its expansion six years later, provide evidence of the perceived importance of physical activities to the mental well-being of the patients. In a similar vein, the erection in 1908-10 of an impressive assembly hall (#15), which was a multipurpose building used as a chapel, auditorium and activity centre, provided architecturally elegant and generous spaces for group indoor social activities. For concerts and other entertainments, this facility could comfortably seat some 600 people.

Medical staff understood that the asylum extended to the limits of the property, and even beyond, for attractive vistas across the surrounding rural landscape and for miles up and down the river were comforting to troubled minds. The provision of manicured formal landscapes, wooded parklands, gardens and groves all contributed to mental recovery. Constructing excellent recreational and social facilities, indoors and out, contributed to the same cause.

While most of the original medical buildings have undergone substantial modification, many elements of this early landscaping and recreational program survive to help understand the role of amusements and the land in treatment. Some of these resources are buildings. Structures such as the assembly hall (#15) and the skating rink (#20) offer an opportunity to understand the importance of recreation and social activities to the treatment program. The tennis clubhouse (#37) is a resource of special interest: though architecturally modest, it is the sole surviving structural evidence available to illustrate an important late 19th century activity, sailing, for it was once the riverside boathouse, which was moved to its present site when the lands south of King Street East were sold.

In general, these built resources have been substantially modified. The skating rink was converted to a curling facility in 1980, and drawings for the conversion suggest that few elements of the early building survive. The task of determining the level of integrity of the surviving fabric (if any) is made more difficult by a lack of early photographs or detailed descriptions in Public Works reports. A survey of the interior has, to date, not been possible.

The landscape itself is of greater significance to understanding early treatment methods. Even if the state of research is not sufficiently advanced to determine the precise nature of the turn-of-the-century landscape program, it is clear that many essential elements have been retained, including the placement of path- and roadways, terracing and some plantings. Outdoor improvements such as the tennis courts (originally to the east of the assembly hall, approximately where the fenced playground behind building #14 now is and now located beside the bowling green) and the green itself also recall the key role of physical activities in recovery.

Service Buildings

Like other provincial hospitals, the BPH was intended to be self reliant. Although it might use public utilities like water and hydro, today the institution has the capacity to sustain itself under the most adverse of circumstances. Continuous programs of maintenance, service and utility provision have always been essential to the operation of such an institution. The patterns of ongoing activity have carved well-used service paths to the rear of the site.

In the 1890s, a series of service buildings was erected to the north (or rear) of the original cottage buildings grouping. This included a carpenter and paint shop (1892), a reservoir (1894) (Figure 23-1 [ORC Fig 6]), a combined carriage house, stable and driving shed (1894), and a water tower. Only the second of these survives (#22; fire hall added 1951). Their construction, however, established a pattern which has held to the present, of placing operational service structures behind the original main complex. Additional facilities were later constructed within this same compound. In chronological order, these include the laundry building (#21, 1127, addition 1954, Figure 23-2 [ORC Fig 13]), the paint shop (#19, 1928), the power house (#43/44, 1934-35), the water tower (1954), the trades building (#27, 1955), and the garage (#28, 1992).

Most of these structures are of utilitarian brick or concrete construction, simply functional boxes representative of industrial construction typical of the time they were built. Among them the power house stands out as a fine melding of architectural design and engineering. Of brick construction marked by large expanses of glass, it reflects the contemporary desire to legitimize then-contemporary engineering by enclosing it with a reasonably sophisticated exterior shell. Very few changes have been made to the exterior of this building, although alterations have been made to accommodate new mechanical systems. The interior of the building retains equipment from each past technology, and is undoubtedly of interest to anyone interested in history of civil engineering.

Landscape Development

In section d) recreational facilities above, attention has been drawn to the interconnections between landscape and therapy. “Moral” treatment regarded peaceful, park-like surroundings as important to the recovery of the mentally ill, while work and recreation in the outdoors contributed to patient well-being. These values are reflected in significant changes in that part of the site to the south of the main hospital complex, modifications which transformed the grounds from “a wild tract of land covered with boulders and weeds” to “a beautiful well-kept lawn” as a result of patient labours.(52) Reference was made to the nature of the various modifications to the property and the role of the medical superintendents (Drs. Murphy and Moher), the head farmers (whose significance is demonstrated by the fact that the institution’s first employee was Mr. D. McCrimmon), and various landscape gardeners (such as the aforementioned Mr. Houston) in planning and carrying out those changes. The relatively high degree of integrity in the parkland character of the surviving landscape contributes strongly to the site’s ability to speak to the theme of the treatment of the mentally ill.

These modifications in the landscape between the ridge and King Street East took place within a larger redevelopment of the site which, over time, included the establishment of agricultural and grazing fields along the east side of the property and the planting of a protective groupings of trees northeast of the eastern-most female cottage. The trees were intended to serve as a windbreak for sitting areas located behind the female cottages. The fields, some of which have since been alienated from the control of the institution, played an important role in the operation of the institution. The products of the fields were utilised in the hospital’s kitchens or were sold in the local marketplace. Proceeds from sales contributed to the financial well-being of the institution. Furthermore, field work for able-bodied patients – some of whom were farmers by profession – was also regarded as therapeutic. Indeed, when additional land was purchased north of the asylum in 1910, nine patients were quickly transferred to live with two attendants at the new Stagg farm.(53) This program of rural, non-institutionalized life was later expanded, an indication that “moral” treatment could effectively take place outside the asylum proper.

As treatment approaches changed in the 1940s and 1950s, the focus on the site shifted from landscape as therapy to landscape as an environment within which medical treatment took place. In the process, much of the original character of the property was retained, presumably because this character was understood and appreciated. The network of road- and pathways remains largely intact, and elements no longer used – such as the pathway which formerly led from the women’s cottages along the eastern side of the front lawn to a gateway along the front fence -can still be identified. The system of terraces continues to showcase the main grouping of medical buildings. Several early recreational landscape features – including the lawn bowling green, the tennis courts and the baseball field – continue in use, while some of the initial plantings have been retained. Overall, the nature of the original asylum landscape, of a mixed wooded and grassed parkland characteristic of Edwardian estates, continues to represent the first decades of the institution’s existence

CULTURAL LANDSCAPES

Cultural landscapes are natural areas on which the imprint of human activities is clear and fixed. Such a broad definition invites refinement: cultural landscapes are of importance when they illustrate, in an understandable and evocative manner, significant human activities. To explain these activities effectively, cultural landscapes must be coherent and continuous; that is, a series of unconnected sites, however linked they may be thematically, cannot constitute a single cultural landscape.

The Brockville Psychiatric Hospital is a evolved cultural landscape which consists of natural and cultivated site elements combined with a large number of structures which date from the founding of the institution to 1992. Together, these resources speak directly to the changing nature of the treatment of the mentally ill over more than a century of use. The ridge-top grouping of asylum buildings and its associated landscape elements – including the front lawn and the adjacent farm fields – illustrates the “moral” treatment approach taken before the Second World War. New construction and extensive renovations undertaken to the main hospital buildings after the war reflected fundamental modifications in medical treatment, signalling the transformation of the institution from an asylum to a mental hospital.

An important aspect of coherent cultural landscapes which occur within restricted property boundaries – such as the Brockville Psychiatric Hospital – are viewplanes, visual axes which help to illustrate aspects of the site’s heritage character. There appear to be eight viewplanes at the BPH. [Discussion and illustrations of viewplanes omitted.]

CONCLUSION

BPH consists of a distinctive landscape, marked by its gentle rise from the highway north to a transverse ridge on which sits an impressive collection of hospital buildings. As a comparison of Figures I and 25 [missing] shows, this has consistently remained the institution’s dominant site feature.

- 1900-1910 – the initial institutional landscaping of the site,

- 1911-1927 – the repair of existing fabric and completion of the institutional plan, 1928-1934–the Depression years of restraint,

- 1935-1952–a period of repair and maintenance of existing fabric,

- 1953-1959 – renovation of existing fabric, expansion, fireproofing and modernization 1960-present – a period of maintenance and modernization, largely in services

While evidence of each of these periods is visible on today’s site, the main buildings are characterized more by extension and renovation during the 1950s than by their period of origin. Secondary facilities — agricultural, recreational and service — are less prominent, but continue to reflect the site’s longstanding functional definition, and sometimes its original fabric. The hospital’s grounds also retain the outlines of their original form.

ENDNOTES

- Ontario Realty Corporation records document 46 administrative building units on the site, but a single continuous structure may have several numbered segments for administrative purposes: the main hospital building, for example, includes 11.

- The province originally expropriated a total of 217 acres of land from two owners: 110 acres, commonly known as the “Picken’s Point” property, was expropriated in 1892 from the estate of David Ogden Ford. This consisted on a 20 acre block between the St. Lawrence River and the Prescott Highway (now King Street East) and a further 90 acres north of the roadway, extending from the highway back to the right-of-way of the Grand Trunk Railway. This is the original site, measuring (including the roadway) 1000 feet wide and 3700 feet in depth, which was described as the asylum site by the Chief Architect, Kivas Tully, in his annual report for 1892; see “Report of the Architect” in Report of the Commissioner of Public Works for the Province of Ontario for the Year Ending 3P December, 1892 (Toronto: Warwick and Sons, 1893), p. 12. The expropriation is documented in Leeds and Grenville County Registry Office, Elizabethtown Township, Lot 6, Concession 1, record of transactions. A further 97 acres to the east of the Picken’s Point property was expropriated from J. J. Henderson in 1893. Sixty acres of this original expropriation was located north of the Grand Trunk Railway tracks, and no evidence has surfaced to indicate that it was ever used for Asylum purposes, except for farming. See the account of this expropriation in a ca. 1892 article, “A Home for the Unfortunates,” whose original source is unknown, p. [1]. A copy of this important and authoritative source is located in the records of the “Book of Memories” project, Brockville Psychiatric Hospital.

- The first intimation of government plans to construct an asylum in or near Brockville apparently dates to 10 December 1884, when the Brockville Recorder newspaper reported that the rumours of the future opening of such an institution in or near Brockville “is without a word of truth.” When the sum of $70,000 was placed in the provincial Estimates for fiscal year 1892 to plan a new asylum for Eastern Ontario, the member of the Legislative Assembly from Brockville, the Hon. Christopher F. Fraser (member, 1875-1894), who was then the Commissioner of Public Works, was credited by the Brockville Recorder in its 17 February 1892 edition with arranging the placement of the asylum within his riding. Fraser is also credited with this coup in “A Home for the Unfortunates,” p. [1]. An early historian of treatment for the insane, A. E. Lavell, stated the following: “Why it was decided to place the new institution on the extreme southern corner of this asylum district [which included the eight most easterly counties], and only fifty miles from the one at Kingston, is not as yet disclosed by any discovered document. The Brockville Recorder credits the choice to the Hon. C. F. Fraser, Minister of Public Works, a native of the town and its local member.” See University of Toronto, Thomas Fisher Rare Book Room, Alfred E. Lavell, Draft of a History of the Ontario Hospitals, also known as Chronicles of the Ontario Hospitals, Manuscript Collection 108, Box I, folder 13, p. [1].

- “Report of the Architect” in Report of the Commissioner of Public Works for the Province of Ontario for the Year Ending 31″ December, 1892 (Toronto: Warwick and Sons, 1893), p. 12.

- The most influential force in the design of late 19th-century asylums, Dr. Thomas Kirkbride, placed considerable emphasis on the appropriate locating and siting of the institution, advocating a rural situation overlooking water near an urban centre. See Thomas Kirkbride, On the Construction, Organization, and General Arrangements of Hospitals for the Insane (Philadelphia: Lindsay & Blakiston, 1854) and the discussion of his philosophy of asylum design in Nancy Toles, A Generous Confidence: Thomas Story Kirkbride and the Art of Asylum-Keeping, 1840-1883 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984). Kirkbride’s influence in Ontario asylum design is discussed in Jennifer McKendry, With Our Past Before ( ‘s: Nineteenth-Century Architecture in the Kingston Area (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1994), Chapter 6, “Controlling Society through Architectural design,” pp. 187-204.

- BPH was originally located on the south half of lots 5 and 6, l’ Concession, Elizabethtown Township. Portions of the original property have been alienated. Oxford Street, the western boundary of the BPH property, is also the municipal dividing line between the city of Brockville and Elizabethtown Township. See Illustrated Historical Atlas of the Counties of Leeds and Grenville, Canada West (Belleville: Mike Publishing, 1976), p. 57. From its founding, the asylum’s traditional associations have always been with the city of Brockville.

- Electronic communication from Doug Grant, Brockville, to Heritage Research Associates Inc., 6 August 1999. We are grateful to Mr. Grant for pointing this parallel out to us.

- Archives of Ontario, Department of Public Works, Contracts, RG15-55-1, Container 5, file 607, contract for the Brockville Asylum, 3 October 1892 “to build the Main and Central Buildings, Kitchen, Laundry, Boiler House, Coal Vault and Six Cottages to be erected near Brockville on Lot 6, 1′ Con., Elizabethtown Township.”

- Archives of Ontario, Records of the Department of Public Works, Correspondence of the Chief Architect, RG15-18-1, Box 4, files 4-5 to 4-9 deal with the construction of the first set of asylum buildings at Brockville and contain considerable correspondence detailing the contracting of local firms for all kinds of work at the asylum.

- Brockville Recorder, 17 February 1892.

- Archives of Ontario, Records of the Department of Public Works, Contracts, RG15-55-1, Container 6, File 730, contract with Thomas A. Fitzgibbon, builder, for a residence for the Medical Superintendent, Brockville, 26 May 1896. There is no contract, but extensive correspondence, on the construction of the Amusement Hall; see Archives of Ontario, Records of the Department of Public Works, Correspondence of the Chief Architect, RG15-18-1, Box 10, files 10-8 and 10-9, Incoming Correspondence, Brockville Hospital, 1909-1914, where the contractor is identified as W. P. Driscoll of Brockville. Inspectors’ reports and newspaper accounts indicate that asylum patients did much of the actual constructional work under the contractor’s direction.

- Adrian Ten Cate and H. Christina MacNaughton, eds., Brockville: A Pictorial History (Brockville: Hanson and Edgar, 1972), p. 146.

- Brockville Recorder, 7 February 1892

- Dr. R. Draper and Dr. D. Nadon, “The Development of Asylums in Ontario: With Special Reference to the Asylum for Eastern Ontario at Brockville,” undated (ca. 1992) unpublished paper, filed with the “Book of Memories” Project, Brockville Psychiatric Hospital, pp. 21-22, citing the “Second Annual Report of the Medical Superintendent of the Brockville Asylum,” 1896.

- Dr. R. Draper and Dr. D. Nadon, “The Development of Asylums in Ontario: With Special Reference to the Asylum for Eastern Ontario at Brockville,” undated (ca. 1992) unpublished paper, filed with the “Book of Memories” Project, Brockville Psychiatric Hospital, pp. 16-17.

- These are the opening words of the article, “A Home for the Unfortunates,” p. [1].

- Brockville Illustrated 1894, Its Growth, Resources, Commerce, Manufacturing Interests, Educational Advantages; Also Sketches of the Leading Business Concerns which contribute to the City’s Progress and Prosperity (Brockville: Benjamin and Davie, 1894), pp. 20-21.

- Dr. R. Draper and Dr. D. Nadon, “The Development of Asylums in Ontario: With Special Reference to the Asylum for Eastern Ontario at Brockville,” and Dr. D. Nadon and Dr. R. Draper, “Brockville Psychiatric Hospital: The First Patients,” both prepared in 1992. It is not clear if either was published, though they both were clearly prepared with a view to publication. Copies of both are on file in the “Book of Memories” Project, Brockville Psychiatric Hospital.

- As Jennifer McKendry has alluded to (in her With Our Past Before Us: Nineteenth-Century Architecture in the Kingston Area [Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1995], Chapter 6, “Controlling Society through Architectural Design,” pp. 190-91), the 1855 plans prepared by the Montreal firm of Hopkins, Lawford and Nelson for the proposed “criminal lunatic asylum” at Kingston (Rockwood) were rooted in part on the tenets of “heroic” treatment, which dominated mainstream medical opinion during the first half of the 191° century. On the “heroic” approach to metal illness, see Michael Donnelly, Managing the Mind: A Study of Medical Psychology in Early Nineteenth-Century Britain (London: Tavistock Publications, 1983). For the types of structures erected to serve the tenets of “heroic” treatment, see John D. Thompson and Grace Goldin, The Hospital: A Social and Architectural History (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1975), pp. 75-76

- “Moral” treatment was a major shift from earlier, “heroic” approaches to the handling of the mentally ill. “Heroic” treatment was based on the notion that the patient’s disturbed mental state could most effectively be rebalanced by physically shocking the individual back to normal. These “shocks” to the system included burning (blistering), bleeding, whipping and quick immersions in cold baths. The use of force and physical restraint were integral parts of “heroic” treatment, and buildings erected to accommodate its techniques most closely resembled prisons in their architectural character. As Jennifer McKendry has alluded to (in her With Our Past Before Us: Nineteenth-Century Architecture in the Kingston Area [Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1995], Chapter 6, “Controlling Society through Architectural Design,” pp. 190-91), the 1855 plans prepared by the Montreal firm of Hopkins, Lawford and Nelson for the proposed “criminal lunatic asylum” at Kingston (Rockwood) were rooted in part on the tenets of “heroic” treatment, which dominated mainstream medical opinion during the first half of the 19th century. On this subject, see Michael Donnelly, Managing the Mind: A Study of Medical Psychology in Early Nineteenth-Century Britain (London: Tavistock Publications, 1983). For the types of structures erected to serve the tenets of “heroic” treatment, see John D. Thompson and Grace Goldin, The Hospital: A Social and Architectural History (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1975), pp. 75-76. The rise of “moral” treatment is broadly connected with the influence of the American alienist, Dr. Thomas Story Kirkbride, who developed an overpowering influence in the handling of the insane and, especially, the type of hospital design required, in North America. Sources on this alternative treatment are cited in the note following.

- .For the character of “moral treatment,” there is an extensive literature. This synopsis is drawn from two informative sources, Nancy Tomes, A Generous Confidence: Thomas Story Kirkbride and the Art of Asylum-Keeping, 1840-1883 (2 Vols., Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984) and Jennifer McKendry, With Our Past Before Us: Nineteenth-Century Architecture in the Kingston Area (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1995), Chapter 6, “Controlling Society through Architectural Design.”

- Dr. R. Draper and Dr. D. Nadon, “The Development of Asylums in Ontario: With Special Reference to the Asylum for Eastern Ontario at Brockville,” unpublished paper (1992), filed with the “Book of Memories” Project, Brockville Psychiatric Hospital, pp. 25-26.

- The signal importance of the institution at Kingston is underlined in Jennifer McKendry, With Our Past Before Us: Nineteenth-Century Architecture in the Kingston Area (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1995), Chapter 6, “Controlling Society through Architectural Design,” esp. p. 202, where the original Rockwood hospital is described as being “this nearly perfect asylum.” This is a somewhat more balanced version of the same author’s “An Ideal Hospital for the Insane? Rockwood Lunatic Asylum, Kingston, Ontario,” Society for the Study of Architecture in Canada, Bulletin, Vol. 18, No. 1 (March 1993), pp. 4-17.

- James De Jonge, “Former Provincial Lunatic Asylum, Saint John, New Brunswick,” unpublished paper, Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada, Agenda Paper 1998-28, pp. 669-720; the quotation is on pp. 688-89. The fate of the Saint John institution was determined during a conversation with Mr. De Jonge, 23 July 1999.

- Dr. R. Draper and Dr. D. Nadon, “The Development of Asylums in Ontario: With Special Reference to the Asylum for Eastern Ontario at Brockville,” unpublished paper (1992), filed with the “Book of Memories” Project, Brockville Psychiatric Hospital, p. 25.

- The literature on these subjects is considerable; for a lucid introduction, see Tom Brown, “Shell Shock in the Canadian Expeditionary Force, 1914-1918: Canadian Psychiatry in the Great War,” in Health, Disease and Medicine: Essays in Canadian History, ed. Charles G. Roland (Toronto: Clarke-Irwin for the Hannah Institute for the History of Medicine, 1984), pp. 308-332.

- See John T. Goodman, “Mental Health,” Canadian Encyclopedia, 1985 ed., Vol. 2, pp. 1336-37.

- These are the main considerations revealed by Harvey G. Simmons, Unbalanced: Mental Health Policy in Ontario, 1930-1989 (Toronto: Wall and Thompson, 1990).

- British North America Act, 30-31 Vic. Cap 3, Section 92, sub-section 7.

- The first legislation merely permitted local authorities “to make provision for the relief of destitute lunatics in the Home District,” and legislation in the following decade was simply permissive. But prevailing opinion seems to have resisted this dependence upon local authorities and pressed for central over local administration. A resolution to commit the sum of £3,000 towards the erection of a provincial asylum passed by an overwhelming majority. For the history of early Ontario legislation towards the support of the mentally ill, see Henry M. Hurd, ed., The Institutional Care of the Insane in the United States and Canada (1916-17, rep. New York: Arno Press, 1973), Vol. 4, pp. 120-129.

- On the expansion of the system, see Henry M. Hurd, ed., The Institutional Care of the Insane in the United States and Canada (1916-17, rep. New York: Arno Press, 1973), Vol. 4, pp. 129-198. See also Hospitals Division, Department of Health, The Hospitals of Ontario (Toronto: Herbert H. Ball, 1934), Chapter 6, “Mental Hospitals.” pp. 235-73.

- This is based on the pattern of establishment and growth described by Pat Mills, Asylums: A Social and Architectural History Concerning Provincially Owned Medical Institutions Built in Ontario Before 1945 (Toronto: Ministry of Citizenship and Culture, 1982).

- The Connecticut institution is described and illustrated in Henry M. Hurd, ed., The Institutional Care of the Insane in the United States and Canada (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1916), Vol. 2, pp. 103-115.

- .For the Hamilton building, see Henry M. Hurd, ed., The Institutional Care of the Insane in the United States and Canada (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1916), Vol. 4, p. 166

- On this subject, see the authoritative study by Leslie Maitland, Queen Anne Revival Style in Canadian Architecture (Ottawa: Parks Canada, 1992) and John Blumenson, Ontario Architecture: A Guide to Styles and Building Terms, 1784 to the present (Toronto: Fitzhenry and Whiteside, 1990), Chap. 12.

- For full details of this work, see Report of the Minister of Public Works for the Province of Ontario for the Twelve Months Ending March 31st, 1959 (Toronto: Baptist Johnson, 1959), p. 63, where the work is described as “the complete renovation and fireproofing of the Elmgrove Dormitory Addition.”

- The contract for the construction of all the farm buildings was signed on 12 May 1894, well before tenders were called for the main hospital structures; see Management Board of Cabinet, Ontario Realty Corporation, Central Drawing Files, signed plans for the bank barn and gardener’s residence.

- See “A Home for the Unfortunates,” from an undated (ca. 1894) issue of Progressive Business News, p. [2]. A copy of this article was kindly provided by the “Book of Memories” Project, Brockville Psychiatric Hospital; a copy also exists at the Brockville Museum.